News outlets around the world have been covering the coronavirus extensively this past week. The coronavirus virus originated in Wuhan, China, and has been declared a global health emergency by the World Health Organisation. The virus, which has claimed 213 lives in China, has spread to 18 other countries. Understandably media coverage has been intense, but with an unacceptable angle: xenophobia.

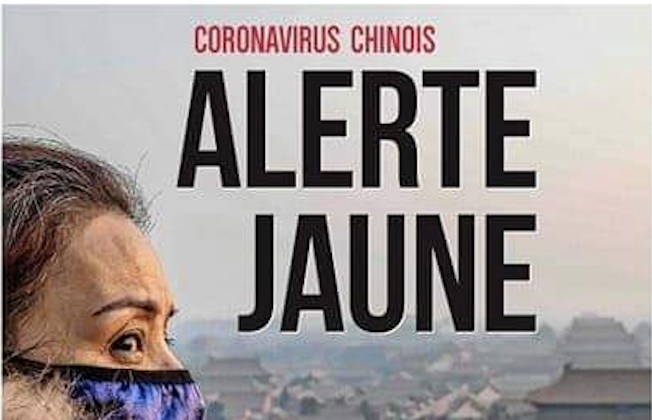

French newspaper Courrier Picard carried two troubling headlines about the virus: “Yellow Alert” and “New Yellow Peril?” both run alongside an image on a Chinese woman wearing a face mask. The paper was quickly called out for its offensive language, and spurred an online movement around the hashtag #JeNeSuisPasUnVirus (‘I am not a virus’), with French Chinese citizens sharing their dismay with the papers language. The term Yellow Peril is a racist metaphor historically used to convey that people of East Asian descent are an existential danger to the Western world. In Australia, the Herald Sun ran the headline: “China virus pandemonium” and the Daily Telegraph on their front page urged “China kids [to] stay home.” A petition was launched on change.org by Wendy Wong to demand apologies from the papers. On the petition, which now has over 54,000 signatures, Wong explains how the Herald Sun has “inappropriately labelled the Coronavirus by race” and The Daily Telegraph “misled the public and caused potential high risk of discrimination against the Aussie kids with Chinese background at school. This label is downright offensive and unacceptable racial discrimination.”

On Instagram, the University Health Services at University of California, Berkeley shared a post outlining common reactions to the coronavirus outbreak. Anxiety and hyper-vigilance were on the list, as well as xenophobia. According to the post, “fears about interacting with those who might be from Asia and guilt about those feelings” is an acceptable response. The post normalised xenophobia and racism against people of Asian descent, and understandably received much backlash.

Xenophobic language and sentiments in the media have real-life affects. There have been many reports of Chinese people, or those who are perceived to be Chinese, facing discrimination abroad. Writing for the Guardian, Sam Phan relays their experiences in recent days in the UK, with people refusing to sit next to them and overhearing advice not to visit Chinatown in London. “This week, my ethnicity has made me feel like I was part of a threatening and diseased mass. To see me as someone who carries the virus just because of my race is, well, just racist,” they share.

“No Chinese, we sorry”, “Dear customers, our restaurant do not accept guest from China. Thank you for understanding”: these were signs spotted in Vietnam and shared on social media. The Evening Standard shared a cartoon to commemorate Chinese New Year depicting a rat (this year’s Chinese zodiac animal) wearing a facemask, alluding to the coronavirus outbreak. The hashtag #ChineseDon’tComeToJapan has been trending on Twitter. Speaking to Le Monde Minh, who is of Vietnamese descent, shared how a driver shouted at her from his car: “”Keep your virus, dirty Chinese!” You’re not welcome in France.” Unfortunately, these are just some examples of what people have endured these past few days. A quick search on Twitter will bring up countless of posts from people sharing the xenophobia and racism experienced around this matter.

Anxiety around the coronavirus is more than understandable, and officials have been putting practices in place to ensure the virus does not spread beyond control. As daunting as the situation may seem, xenophobia is not an acceptable response. Using the coronavirus to make racist and xenophobic remarks about Chinese people is unacceptable, especially when it comes to the press who have a duty to inform the public, not demonise a whole subset of people.