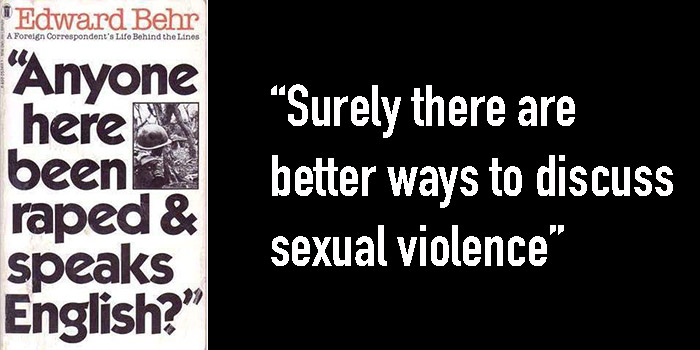

After a long career of working as a foreign correspondent covering war zones, Edward Behr published his memoirs with the disturbing title, Anyone Here Been Raped and Speaks English?

Unfortunately, Behr’s title is far too familiar for most foreign correspondents. We have all watched our colleagues rush into conflict zones, eager to get stories that show the face of war without accounting for whether or not this actually serves victims of war themselves. Surely there is a better way to do this kind of journalism—a way that actually gets stories into the world, asks for justice, and makes it worth a survivors time to share their story in the first place. While the more moral among us tell ourselves that this is the best way to record atrocities—and ensure that there is not a culture of impunity—the reality is that journalists are often the first people to talk to victims of war, often with little training or background in how to speak with victims of trauma. Some organisations like the DART Center are trying to fix this—but their trainings hardly reach every journalist covering these issues around the world.

It isn’t only journalists who are the careless ones—NGOs, eager to get their work into the mainstream media gather sexual violence survivors willing to speak to the press, and line up journalists to do interviews. Meanwhile, survivors are reliving their trauma, over and over again with each interview.

How can journalists tell stories about sexual violence—which is important, particularly in understanding war, and ending impunity—while still respecting a duty of care towards survivors? This was the topic of a recent panel titled Reporting Sexual Violence in Conflict at the Frontline Club in London.

“It worries me that we are re-traumatizing people,” said Sunday Times correspondent Christina Lamb, who has worked in conflict zones ranging from Northern Iraq to the Democratic Republic of Congo.

What is more, Lamb brought up that what a sexual violence survivor tells a journalist—and how the journalist uses this information in their report—can also harm their legal case, if they have the opportunity to bring their perpetrator to trial. This brings up the case that journalists not only need trauma training, but also legal training to know whether their reports are doing more harm than good.

“We need to get the stories out if there is going to be an end to the impunity, but we need to do it in a way that survivors feel comfortable, and doesn’t harm them.”

So, if a journalist is going to interview a sexual violence survivor, how can they go about doing so without doing harm?

First, it is important to establish informed consent. While many journalists see this as a checklist—which is taken care of the minute that someone signs a release form, or gives their fingerprint—ethically it should be a much more informed process. Does the interviewee realize that this report will be shared online, and travel across social media to people in their community? Do they realize what are the potential consequences of sharing their story? Could this destroy a legal case—or worse, result in further violence and repercussions for themselves, or their family?

During the Q&A, several people brought up that this varies from country to country, and context to context. How do you inform someone who is illiterate? How do you bring up difficult conversations about repercussions—which could change whether or not someone consents to sharing their story?

Second, let them be in control of the interview. Often times, a sexual violence survivor—particularly a repeat sexual violence survivor, as is often seen in war zones—has been conditioned to think that they cannot say no, sometimes making them give their consent to a journalist before they are ready. This is where trauma training is useful—what does their body language say? Are they ready to share this part of their story? Make sure that the interviewee knows that they can always back out, and don’t have to share their story in its entirety.

Lastly, how can journalists be more creative about how to tell these stories? If a survivor tells their story once, it should be enough; they shouldn’t feel pressured to repeat it for hundreds of different channels and newspapers. Is there a way that these testimonies can be gathered together, prioritizing duty of care to the source over media outlets’ competition with one another? We need to be thinking more creatively about how to do our journalism, and value the story.

“Conflict-related sexual violence must be covered in the media. If it is not, survivors will continue to be silenced and impunity will reign forever,” said Leslie Thomas, another panelist who is the director of the film The Prosecutors.

“It is also essential that the way that we cover war crimes do not harm those who have already been directly harmed. I believe in working together, members of the media, survivors, advocates, lawyers and social workers can surface challenges and find solutions.”

Do you have creative ideas or solutions? Perhaps you have resources that you recommend, or suggestions for newsrooms that should undergo these kinds of trainings. Let us know on social media with the hashtag: #ReportingTrauma.

Read more about the #EthicsofCare here.