Published: 1 June 2011

Published: 1 June 2011

Location: UK & Worldwide

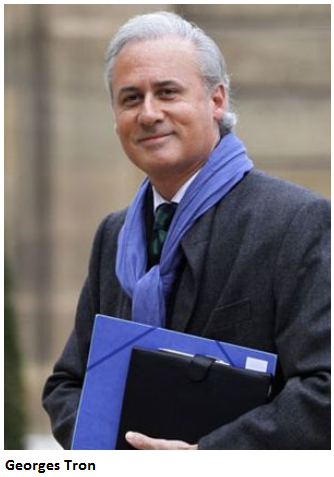

The news that Georges Tron, a civil service minister in Nicolas Sarkozy’s government, is being investigated for sexual harassment, adds fuel to the smoldering fire started by Dominique Strauss-Kahn’s arrest in New York a couple of weeks ago. The French, it appears, may be learning one of the more recherché lessons about globalisation – that it makes the suppression of awkward truths a lot harder.

I don’t know whether Tron is guilty or not – he, at least, strongly denies the accusations of two women who claim that he and a female accomplice sexually harassed them on a number of occasions over a period of three years. I don’t know whether DSK is guilty. But I do know that these incidents have drawn aside a curtain that the French media and the political establishment have tried for years to keep tightly closed.

The first time most people outside France became aware of the country’s attitude to privacy was probably in 1994, not long before the then president, François Mitterrand, died of prostate cancer. The French gossip magazine, Paris Match, ran a cover showing a grainy paparazzi picture of the president and a young woman leaving a Parisian restaurant. The young woman was Mitterrand’s daughter Mazarine by his long time mistress, Anne Pingeot.

France’s politicians and journalists were familiar with the story of Mitterrand’s two families. Mitterrand himself was long known to be a “dedicated womanizer”, as the London Sunday Times observed in 1994, but the French media kept quiet about it. Even when Mitterrand acknowledged Mazarine in the pages of Paris Match, the magazine ran their inside story under the sentimental banner “The moving story of a double life”. And so the idea of France’s sophisticated and entirely non-prurient attitude to their politicians’ peccadilloes was born.

Actually, it’s more complicated than that because, since 1970, the French have had a fairly comprehensive privacy law which states that “everyone has the right to respect for privacy” and carries heavy penalties – including damages and up to a year’s imprisonment for individuals found guilty of intruding into someone’s private life. Of course, the French media could have fought this law, on the grounds that a politician’s actions are always a matter of public interest. In Mitterrand’s case, this was certainly true – after all, he used public money to pay for his second family’s protection by an anti-terror unit and to accommodate them in presidential palaces – but the law has never been seriously opposed precisely because, at some level, the French media believe that the principle of protecting the privacy of public figures is right.

“It’s a democratic principle – hypocritical in some people’s eyes, but fundamental,” says Nicholas Demorand, editor of the left-wing French daily newspaper, Libération. “Ditching this principle would lead to encouraging short-term buzz and trash over quality news.”

Another former president, the patrician Valéry Giscard d’Estaing, understood. “It was the honour of the French press that the lives of politicians were kept out of the media,” he once said.

Now, let’s be honest about this. Keeping the lives of politicians out of the media has meant, in every case I can remember, keeping the truth about sexual antics and the corrupt practices that often accompany them away from the prying eyes of the public. And, of course, the vast majority of cases are about male politicians. Well, now another well-known lothario, DSK, joins Mitterrand in the incontinence hall of fame and, thanks to a chambermaid in New York who – not being French and having no idea of DSK’s identity or how powerful he was – blew the whistle. And that whistle has already started to reverberate.

meant, in every case I can remember, keeping the truth about sexual antics and the corrupt practices that often accompany them away from the prying eyes of the public. And, of course, the vast majority of cases are about male politicians. Well, now another well-known lothario, DSK, joins Mitterrand in the incontinence hall of fame and, thanks to a chambermaid in New York who – not being French and having no idea of DSK’s identity or how powerful he was – blew the whistle. And that whistle has already started to reverberate.

At first, we heard from more women who had crossed DSK’s path. Journalist Tristrane Banon alleged an attempted sexual assault, while a Hungarian-born economist, Piroska Nagy, accused him of sustained harassment when she worked at the IMF. Soon everyone seemed to be claiming that they had known all about DSK, the Great Seducer, for absolutely ages. He was, they all agreed, “un lapin chaud” – a metaphor that seemed to make things alright – except, of course, for those who knew what it was like to be subjected to the importunate advances of a hot bunny.

“When I see that a little chambermaid is capable of taking on Dominique Strauss-Kahn,” one of Georges Tron’s accusers said in Le Parisien, “I told myself I did not have the right to stay silent. Other women have perhaps suffered what I have suffered. I have to help them. We have to smash this omerta.”

The omerta, the silence, she refers to is too often justified by an appeal to privacy. And privacy is important for all of us. But in the cases of those powerful men who hide behind its skirts, privacy does not justify criminality, corruption or harassment. “The French media’s respect for privacy now looks more like an exaggerated defence towards the rich, powerful and macho,” according to Camilla Cavendish in The Times. “French politicians, including Mr. Strauss-Kahn, have enjoyed too much protection from a deferential public and media.”

But using privacy to defend corruption, criminality or simply the exploitative power of men is not an exclusively French phenomenon.

You might think that Italian Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi rather enjoys his reputation for “bunga bunga” parties and teenage prostitutes – and maybe it does draw the attention of  the media (most of which he owns or controls) away from thoughts of political and financial corruption. But if anyone threatens to dig real dirt on Berlusconi’s extracurricular activities, he shouts “Foul!”. Two years ago, for example, he filed a complaint under Italy’s privacy law against a photographer who took paparazzi pictures of a party at his Sardinian villa. Rumour suggested that the reason was the presence of an aspiring teenage model, Noemi Letizia. At the time, Berlusconi’s second wife Veronica Lario – who surely knows a few secrets – had begun divorce proceedings against her husband, telling one newspaper that she could not stay with a man who “consorted with minors”.

the media (most of which he owns or controls) away from thoughts of political and financial corruption. But if anyone threatens to dig real dirt on Berlusconi’s extracurricular activities, he shouts “Foul!”. Two years ago, for example, he filed a complaint under Italy’s privacy law against a photographer who took paparazzi pictures of a party at his Sardinian villa. Rumour suggested that the reason was the presence of an aspiring teenage model, Noemi Letizia. At the time, Berlusconi’s second wife Veronica Lario – who surely knows a few secrets – had begun divorce proceedings against her husband, telling one newspaper that she could not stay with a man who “consorted with minors”.

Defending privacy may be the justification for resorting to legal action as Berlusconi has done, but in an unequal society the law does not defend all citizens equally. As the celebrated English lawyer, F.E.Smith (later Lord Birkenhead) is reputed to have said, “The law in England is open to everyone, like the Ritz Hotel”. Privacy offers the best possible demonstration that this bon mot is true. English law recognises no specific right to privacy and the use (or threat) of libel actions to gag the press should be proof enough that the protection of privacy in England is a benefit disproportionately enjoyed by those who can afford to pay for it. Libel cases heard in the English courts commonly rack up legal costs in the hundreds of thousands of pounds, regardless of who wins.

A cheaper approach to the legal enforcement of privacy in England is offered by super- injunctions and anonymised injunctions. These controversial instruments effectively ban the identification of the individuals they protect. They can cost up to around £50,000, so they also tend to be sought by wealthier individuals and corporate bodies. In recent months, they have been awarded to businessmen like the former head of the Royal Bank of Scotland, Sir Fred Goodwin, high earning footballers like John Terry and Ryan Giggs, and at least one journalist – Andrew Marr – all of whom sought to hide their sexual misdemeanours from the public gaze. One can be forgiven for thinking that these legal instruments have been designed to help men in the public eye avoid the stigma of their sexual shenanigans.

injunctions and anonymised injunctions. These controversial instruments effectively ban the identification of the individuals they protect. They can cost up to around £50,000, so they also tend to be sought by wealthier individuals and corporate bodies. In recent months, they have been awarded to businessmen like the former head of the Royal Bank of Scotland, Sir Fred Goodwin, high earning footballers like John Terry and Ryan Giggs, and at least one journalist – Andrew Marr – all of whom sought to hide their sexual misdemeanours from the public gaze. One can be forgiven for thinking that these legal instruments have been designed to help men in the public eye avoid the stigma of their sexual shenanigans.

It certainly looks like we’re in the midst of a shenanigan tsunami – and I haven’t even mentioned Arnold Schwarzenegger, the “Gropegate” affair in 2003 when he was accused by the Los Angeles Times of serial sexual misconduct, and the recent exposure of his adulterous relationship with a member of his household staff.

But what’s the lesson here? Attempted rape is very different from a consensual affair, and different again from using prostitutes or maintaining a double life. In some cases, the women involved might actually have been attracted by the sexual magnetism apparently exuded by celebrity and power. It happens. In any case, can we really compare what Ryan Giggs and a minor celebrity from a reality TV show get up to with DSK’s alleged assault on a hotel chambermaid?

The common factor, of course, is that all the cases are examples of straightforward sexual inequality. In one way or another, every one of these cases is an example of the abuse of power. The men have all the power; they have used it to insulate themselves from the ordinary moral world, and they have relied on the law in their attempts to avoid the consequences of their actions.

Strangely, the media coverage of the different incidents has shied away from such an ethical analysis, preferring instead to focus on psychology – the flaws in DSK’s personality, Schwarzenegger’s egomania, or the adolescent fixations of superrich footballers. At the root is an obsession with the privacy of politicians and celebrities. This has helped direct the spotlight of media attention on to the character of individuals and away from the ethical and political context in which power and fame are expressed.

Gary Hermann for the Media Diversity Institute