What is freedom of expression? When is bullying someone in the public interest? The ethics, culture and practices of the British press have been thrown into question once again following the death of Caroline Flack. But, haven’t we asked these exact questions before? And how are we back here?

Caroline Flack’s death is reigniting a public debate about the notorious British tabloid press. Laura Whitmore, who succeeded Flack as host for ITV’s hit show Love Island, stressed the need for change, saying on BBC Radio 5 Live: “To the press, who create clickbait, who demonise and tear down success, we’ve had enough”. Within hours of the news, calls were made for a ‘Caroline’s Law’, insisting that it should be a criminal offence to ‘knowingly and relentlessly bully a person’, referring to the tabloid press persistent coverage of the police investigation into Flack’s alleged assault on her partner. The petition for Caroline’s Law currently has 800,000 signatures at the time of writing.

Labour MP Jo Stevens agreed with the need for change, but also referenced the government’s failure to implement the full recommendations from the Leveson Inquiry, which she said ‘would have looked at precisely the role of newspapers in reporting on this sort of activity’.

The Leveson Inquiry was set up following public outrage and demand for wider media reform following the News International phone hacking scandal in 2011. It laid out two stages of recommendations, which included a new independent watchdog with sufficient powers ‘to carry out investigations both into […] breaches of the code’ and impose fines up to £1 million. These recommendations were hugely popular with the British public at the time, with 79% of those surveyed by YouGov saying they supported an ‘independent body, established by law’ to regulate the press. So have they actually been implemented?

Well, not really. IPSO (Independent Press Standards Organisation) was set up as a direct result of the inquiry, but has received strong criticism for its handling of complaints from individuals affected by press abuse. The second stage was due to investigate the relationship between journalists and the police but was dropped completely by the previous Conservative government.

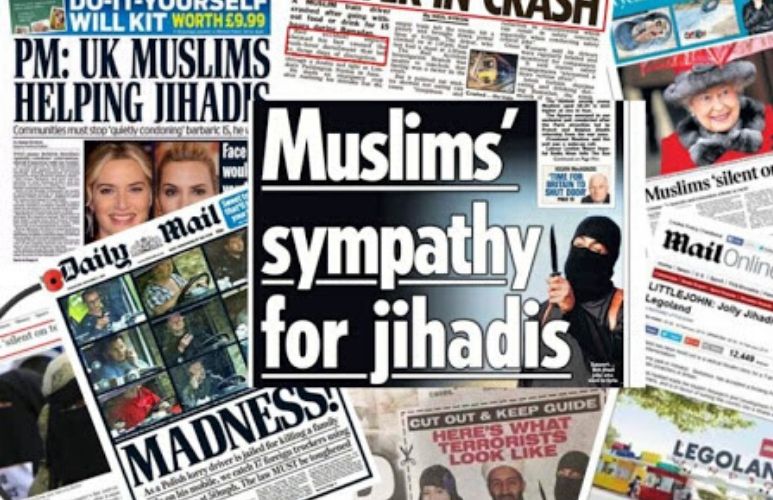

Eight years later, barely anything has changed. IPSO’s ineffectiveness has allowed a continuation of harassment and discrimination, especially against marginalised groups. Hacked Off, a campaign organisation set up to hold the press to account, explained how IPSO’s editors code, specifically Clause 12 of the code, only applies to individuals on accounts of discrimination, meaning that ‘no denigration of a group – women, Muslims, Travellers, trans people or any other – can ever count as discrimination or abuse at IPSO’. They refer instead to IMPRESS, a smaller, independent press regulator who have as article 4.3 in their code:

Publishers must not incite hatred against any group on the basis of that group’s age, disability, mental health, gender reassignment or identity, marital or civil partnership status, pregnancy, race, religion, sex or sexual orientation or another characteristic that makes that group vulnerable to discrimination.

Hacked Off also reported that in 2017, of 8,148 complaints of discrimination that IPSO received, they upheld just the one. This fundamental flaw in IPSO’s standards is what allow articles denouncing ‘The Muslim Problem’ to remain unaltered despite being reported for inciting hatred of a minority community. Similarly, Fatima Manji, a Channel 4 news presenter, questioned IPSO’s response to an article in The Sun which expressed outrage that she was assigned to present coverage of the Nice terrorist attack because she was a Hijab-wearing Muslim woman. Speaking to BBC Radio 4, Manji said: ‘It was upsetting enough to find myself the latest victim to Kelvin Mackenzie’s tirade. But now to know that has been given the green light by the press regulator and that effectively it is open season on minorities, and Muslims in particular, is frightening.’

When Katie Hopkins described migrants as ‘cockroaches’ in an article titled ‘I’d use gunships to stop migrants’, IPSO rejected the complaints. Firstly, because ‘Clause 12 is designed to protect identified individuals mentioned by the press against discrimination, and does not apply to groups or categories of people’, and secondly because ‘although we acknowledge that complainants were offended by the column’s discussion of migrants, the Editors’ Code does not address issues of taste and offence.’ There is nothing wrong then in IPSO’s eyes, says David Leigh of the Guardian with publishing ‘’Wogs, go home’ – or indeed with ‘Juden raus’.

While IPSO have seemingly failed in dealing with the issues of harassment and abuse that the Leveson recommendations were meant to address, the public debate quickly shifted to the necessity of freedom of expression. In 2012, Education secretary Michael Gove accused the inquiry of ‘creating a chilling atmosphere’ towards freedom of expression, suggesting instead, that the concern should be directed towards a few ‘rogue journalists’. Mike Harris of 89up (a campaign group which promotes freedom of speech) commented that ‘investigative journalism will be stopped dead in its tracks when these new laws come into force’. And public opinion backs these concerns, with 48% of people polled in 2018 saying: ‘there are many important issues these days where people are simply not allowed to say what they think.’ It seems reasonable to conclude, that largely through the support of freedom of speech is what ultimately prevented the Leveson inquiry to have the impact it wished for, and why the calls for Caroline’s law will most likely be resisted once more.

Without effective regulation, British tabloids continue to publish content which successfully drives their traffic, despite how discriminatory, or inciteful that content is. And the disturbing irony is despite public opinion strongly supporting press regulation, massive numbers of people still read the content created from the lack of it. Jim Waterson comments that ‘it was the public appetite for details about Flack’s private life that drove the scale of the coverage, with articles about her death topping the “most-read” lists.’ The assault case was justified as being in the ‘public interest’ by the Crown Prosecution Service, which only goes to reminds us about the complexity of the issue, and that to get a regulated press, we still have a mountain to climb.

Click here to support our campaign to get IPSO to change Clause 12 in three easy clicks.