Published: 22 November 2011

Published: 22 November 2011

Region: Germany

By Aidan White

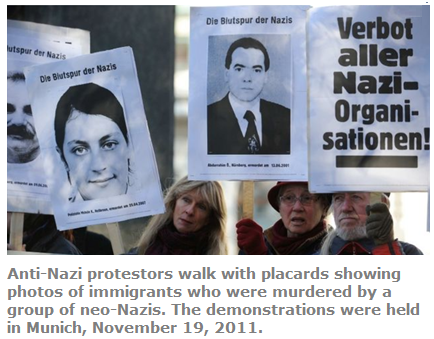

Shocking revelations about a neo-Nazi group in Germany that for ten years engaged in a murderous campaign of violence killing at least ten people has provoked an angry debate about how right-wing extremism as well as racism and xenophobia still infect German society.

For a decade the Zwickau neo-Nazi terror cell, which called itself the National Socialist Underground, carried out a ruthless campaign of targeted killings and armed robberies involving the deaths of nine men of Turkish and Greek origin and a 22-year-old policewoman.

There has been massive criticism in recent days of the negligence and incompetence of police and security services who failed to prevent the murders. There is also anger over the misleading line of inquiry – actively promoted by media – that the murders were the result of infighting among migrant criminal gangs and originated from Turkey.

Equally troubling are claims that government money – totalling hundreds of thousands of Euro – was paid to neo-Nazi informers by the Office for the Protection of the Constitution, Germany’s domestic intelligence agency, and ended up funding activities of the far-right.

While media commentators have solemnly warned politicians against kneejerk reactions, such as banning the far right National Democratic Party (NPD), journalists themselves are coming in for criticism over their reporting of the affair with claims that they downplayed the story and were guilty of latent racism in their coverage.

All media, including the respected news magazine Der Spiegel, referred to the murder spree which began in 2000 as the “doner killings,” in the process creating distance from the community at large, dehumanising the victims and feeding the lie that these gruesome murders were the work of outsiders.

In fact, only two of the victims owned restaurants, the rest were a tailor, a kiosk owner, a key cutter, a grocer and a florist. Germans are being forced to imagine how they would feel if serial-killing of Germans in another country was dubbed the “sauerkraut murders.”

The “doner killings” label fed a stereotype about foreigners being responsible for the crimes and the police added to this when they tellingly codenamed the investigation “Bosporus.”

But the murders were not linked to organised crime stemming from Turkey and they were not bloody confrontations over protection money or drugs or internal shady intrigue. Instead, they were the work of a ruthless gang of home-grown German racists who for years were able to elude arrest thanks to the lack of serious and concerted investigation by the authorities.

The media coverage and the suggestion that foreigners were responsible in turn reinforced a racist narrative that remains strong within the public at large.

According to a 2010 study by the Friedrich Ebert Stiftung, a foundation with links to Germany’s center-left Social Democrat Party, more than a third of Germans believe that the country is in “serious danger of being overrun by foreigners.” A similar number also believes that, when the labor market gets tight, “foreigners should be sent back to their home countries,” and that they many immigrants only came to Germany “to take advantage of the social welfare system.”

For years Germany has lived with a legacy of racial hatred that casts a shadow over the post-Nazi generations. The tendency in public life in recent years has been to avoid confronting the unpleasant truth that race hatred is a poison still at work in German society.

This disregard has led to a lack of focus on the threat from right-wing extremism and has been reflected in the security agenda of the government. In the post 9/11 era German security services have invested heavily in creating a centralised databank of Islamic extremists to counter the threat of terrorism, but nothing similar has been created to identify the members and followers of neo-Nazis networks that still operate in the country.

The failure of media to ask searching questions of the authorities and the tendency to use casual racist language has revealed a weakness in German journalism that may see fresh effort to improve media performance in this area.

In the 1990s German journalists were among the leaders of a campaign organised by the European Federation of Journalists – the International Media Working Group Against Racism and Xenophobia – to raise awareness of media responsibility in coverage of racism. The lessons of the “doner killings” provide a compelling argument for a revival of such work.